Granulation

- Oct 16, 2022

- 3 min read

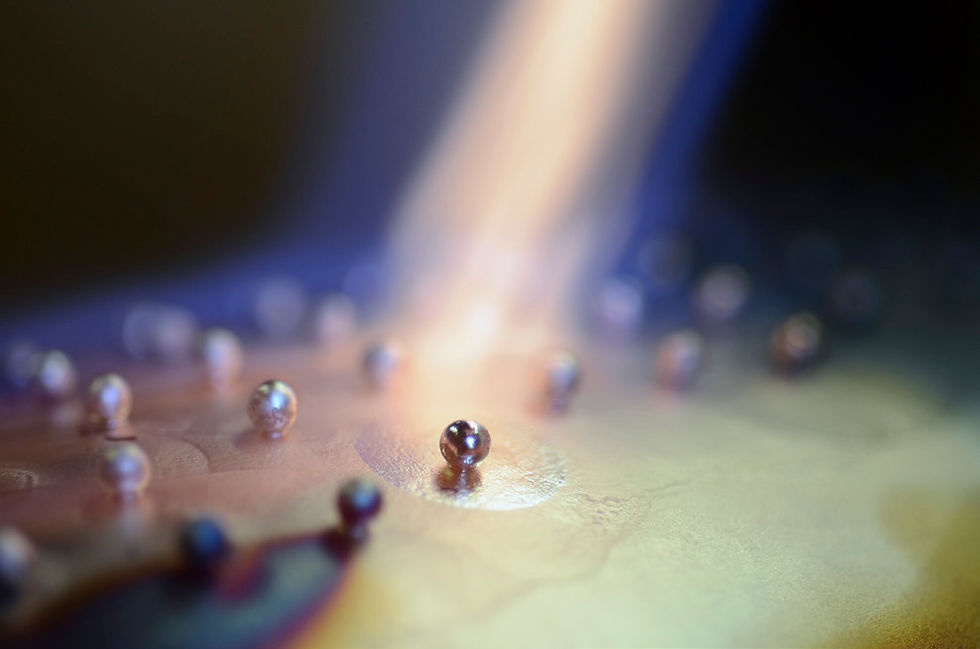

Granulation is a decorative technique whereby multiple gold or silver spheres are attached to the surface to create a specific decoration. Technically, this can be done with or without soldering, but "true' granulation is often associated with not using solder. While possible with traditional soldering, the join formed with traditional granulation (reaction soldering) is much more delicate and hidden.

The earliest evidence of the technique dates back to around 2500 BC in south Mesopotamia. Today the technique is commonly used in both gold and silver jewelry. Gold granulation is usually practiced in higher purity alloys, from 18–22K (750–917).

"True" Granulation, or reaction soldering, does not involve a conventional soldering alloy, but uses a copper salt/glue. It is a form of surface or localized alloying that happens on heating.

Granulation in Gold and Silver

The granules and the "back plate", onto which the granules are attached, must be carefully prepared. For the granules:

Gold or silver granules are made by cutting a coil from a fine wire wrapped around a mandrel.

The wire is then placed in a crucible filled with charcoal powder and heated. As the wire melts, it will form a sphere. A spherical shape minimizes the amount of surface area, and therefore the energy of the alloy. This is often described using the concept of surface tension. The charcoal powder helps to form perfect globe shapes, and helps prevent oxidation.

The granules can then be pickled to remove any surface oxide which may have formed.

For the granulation itself:

The granules can be positioned onto the surface using a water-based glue containing a copper salt and then dried.

They can then be heated and the granules fuse to the piece.

Science of granulation – Reaction soldering

On heating:

(100˚C/212˚F) – Copper salt is oxidized to Copper (II) Oxide.

(600˚C/1112˚F) – The glue burns and carbonizes. This creates a reducing area and converts the copper oxide to a metallic copper.

A thin copper layer forms on the surface of the surface and granules.

(850–890˚C/1562–1632˚F) – The copper diffuses with into the gold or silver surface. This leads to a reduction in the melting point of the alloy.

The two surfaces now have a lower melting point than the rest of the alloy.

The surfaces then melt very quickly, long before the rest of the alloy, and so a metallic bond is formed between the two pieces.

The heat is removed and the join solidifies, with the rest of the alloy "untouched". Thus, we get a self-soldered joint known as reaction soldering or transient liquid-phase bonding.

Forming a solid connection

To ensure a strong bond between the surface and the granules, it is necessary to form a thick enough join between the two of them, known as a "neck".

The correct ratio between energy and time, between the heat and the duration of heating is crucial:

Insufficient heating is insufficient to form a strong connection

Overheating will causes the granules to melt into one another and into the substrate.

The joining phase takes the least time of the entire process of granulation, but at the same time it is certainly the most difficult.

Granulation by plating

Granulation in high-karat gold, and sometimes in silver, is often performed using extra steps.

Instead of using copper salts with the glue, the copper is applied directly to the granules. The copper can be applied by electroplating, using an acidic solution. This allows careful and precise control of the amount of copper applied.

Fully pre-copper plating the granules and the substrate also has some disadvantages, because we cannot remove the excess copper which isn't used to make the connection:

Excess copper causes the surface to sweat.

The whole sample needs heating for the granulation process to work.

Heating an entire sample for decorative granulation is not feasible. Since the granules are not glued onto the surface, the little balls will roll off as soon as the object moves. Even if this is achieved, upo

n heating, the granules will heat quicker than the bulk object. They will quickly come to their melting point and melt away while the surface of the object will not be warmed up enough to make the connection.

It is often easier to heat the object and granules with a large propane/compressed-air flame, traditionally used for annealing and soldering silver hollowware. Using the torch in the “right” way allows to bring only a very small area to the required temperature for granulation.

Common problems

I can't form a perfect globe

This is often because the pieces are too big and consequently too heavy. The pieces will sink to the bottom of the crucible forming granules with a flat surface.

My silver granules splash on the surface during granulation

This is most likely because the granules have absorbed oxygen on heating during forming granules. This is why charcoal is used to create a reducing environment that prevents oxygen being absorbed by molten silver.

I can't make a straight-line row of granules

Fixing the granules to the surface with a liquid-based glue will often lead to the granules clustering. They will tend to form triangles, rosettes or double rows. The granules resting on one another is more stable.

Read more by David Huycke (Santa Fe Symposium):

Comments